Amateur Radio Support for Hospitals

A 38-Year Legacy

How it Began, The Early Lessons Learned

by April Moell WA6OPS

Over three decades ago, a switchboard failure led me to realize the critical importance of communications in medical facilities. It didn't take an earthquake or other major disaster to suddenly put patients at risk that day. And it didn't take a major disaster for my little ham radio set to become a key communications resource. The special organization that was formed thereafter to serve this largely-unfilled mission can serve as an example for Amateur Radio emergency communications groups around the country.

In October 1979, I was the Director of Occupational and Recreational Therapy at St. Jude Hospital in Fullerton, California. Because we live in earthquake country, my husband and I kept our radio equipment handy at work, so we could quickly contact one another if the earth shook. My trusty Drake TR-33 two-meter cereal-box size transceiver was in my desk drawer and my ARES card was in my wallet. What training I had was as a result of performing Red Cross communications during some brush fires. The hospital had an HF ham station, used for Radio Time with patients as part of the hospital's rehabilitation programs. I was ready for an emergency -- so I thought.

When I realized that the central switch had failed and the entire hospital had no working phones, I grabbed my TR-33 and headed for the Administrator's office, thinking I could help. I quickly realized that I didn't really know what I was offering. The ham station in the basement would be of no use, being far from the switchboard and only on the long-distance HF bands. That wouldn't help with unit-to-unit communications nor to contact the local physicians in their offices.

As I reached the Administrator's office, the hospital's Chief Engineer was in the doorway. I showed my rig and offered, "Would you like me to get some radio operators in to help?" The Administrator looked rather quizzically at me for a moment and then said, "Well, I'm not sure we need to do that." The engineer countered with, "Maybe it wouldn't hurt to let some of them come in." I looked over at the Administrator and he nodded.

I quickly made my way through the front entrance and, outside the building, made a call on the ARES repeater. Fortunately, someone I knew answered from his home and volunteered to get help. All I could tell him was that the hospital had no phone service. I waited anxiously in front of the lobby entrance. Eventually, Amateur Radio operators started arriving, some having heard my plea on the radio, and some having been called by the ham who first answered me.

The phones stayed down for about two hours. The radio operators arriving throughout that time had widely varied levels of preparedness. Many I knew. Some I didn't. Their radios served as their identification as I thanked them for coming, directed them into the hospital and on to the switchboard.

Some responders had only their big 70's-vintage HTs. One brought in a pull cart with a mobile rig on it. Another had a large briefcase, like a salesman. For most of the outage, the radio operators were busy trying to get communications established at hospital units that the switchboard operator deemed most important. One left the hospital after twenty minutes because his only HT battery had discharged. A few unit-to-unit messages were handled. Then the phones came back on line.

A Great Response, But ...

Hospital staff members were very impressed that volunteer radio operators could and would come to their facility to help in the middle of a weekday. However, I was breathing a sigh of relief, realizing that it was a rather haphazard response. Most of the operators, myself included, weren't well prepared. It took too long to get reliable internal communications established. The operators weren't ready for an extended outage, if it had occurred. And except for me, no operator had any familiarity with the medical environment, other than perhaps as a former patient. For instance, I was a bit uncomfortable about the hams on a nursing unit not knowing what "stat" meant, and not having any idea what communications would be needed if a Code Blue (life-critical emergency) occurred.

At that point, I had little chance to think all that through, because accolades had started to come my way. An article appeared in the local paper about what I had done with my radio to get ham operators to help, with a photo of me holding my TR-33 while standing in front of the hospital. I was quite pleased because I had done what I had been told by ham leaders was important: "Get publicity for Amateur Radio."

Hospital administrators were so impressed by hams' ability to maintain communications that they contacted the local press. This story appeared in the Fullerton News-Times, a newspaper that is no longer published. Note the reporter's improper use of the possessive. The hospital name is St. Jude, not St. Jude's. It is not to be confused with the hospital of the same name for children in Memphis. Similar stories ran in the Fullerton News-Tribune, the La Habra Star-Progress and the Brea News-Times.

The Emergency Department Supervisor was quite intrigued by what had happened. She came to my office and I ended up presenting a tutorial on Amateur Radio to her. She was extremely interested, especially as I talked about ARES and how we had helped out in wildfires I showed her articles from Amateur Radio publications about responses after tornadoes and hurricanes.

That same Emergency Department Supervisor also served as the hospital's Disaster Coordinator. Next thing I knew, she was asking me to put a group of hams together to help the hospital in an upcoming Orange County disaster drill. My only involvement with disaster planning at that time was to prepare my department for what would happen in our area if a major mass-casualty incident occurred. Our rehabilitation rooms would become holding areas for early discharged patients and less-injured victims awaiting further treatment. My involvement was soon to change.

I contacted our area Emergency Coordinator at the time, Ralph Swanson WB6JBI, to discuss what had happened. With his support. I selected seven ARES members. On the morning of the drill, we all gathered in the east lobby, near the switchboard. That area became the hospital's Emergency Command Post as the drill got underway. Since I knew the facility, I then escorted each ham to locations requested by the Disaster Coordinator.

The simulated scenario began. Notification of incoming ambulances came via landline and a newly-installed county-wide VHF voice and signaling system known as HEAR, the Hospital Emergency Administrative Radio. Within an hour, St. Jude was receiving a large number of victims from the simulated disaster scene. As employees acted out real-time use of the Emergency Department, X-ray, Laboratory and surgical suites, the hams relayed important information between key locations. Our ham outside of the Emergency Department door proved to be a big help, because he provided ambulance arrival information that the command staff had not been able to rapidly ascertain in previous drills.

Mark Shapiro K6OGD (center) is in the middle of the action as HDSCS participates in one of its first Orange County mass-casualty drills back in 1981. He is alerting the hospital Command Post of the arrival of patients by bus and ambulance.

Soon over twenty drill patients were in the facility and more were coming. A bottleneck developed in the hallway outside of Surgery, where there was no telephone. I was asked about putting a radio operator in that location to communicate directly with the Emergency Department. My facilitator/oversight role suddenly disappeared. I reported to the Surgery desk, a nurse quickly joined me, and we went into the hallway by the elevator. The Emergency Department communicator was asked to inform us any time there was a decision to send a patient down to Surgery.

On numerous occasions, the medical staff talked third-party on our radios, deciding whether a patient needed to come directly to Surgery, could be temporarily taken to the Intensive Care Unit, or brought into the Recovery Department and monitored until a surgical suite became available. This made a huge improvement in getting the overload of patients prioritized. Surgery staff members were thrilled.

The late Win Smith W6MBA at the Command Post near the phone switchboard (PBX) during a 1981 drill. Notice the classic nurse headgear.

We all learned a great deal that day. The hospital learned that hams were a communications resource that could be deployed where needed most inside the hospital. The hams learned what it was like to work directly with hospital staff and how an understanding of the medical environment was crucial to best provide communications related to patient care. Although the hospital leaders were impressed with our effort, we realized that to become an integral part of the disaster plan, more education and training would be a must.

From One to Seven

Orange County Emergency Medical Services Agency divides hospitals geographically into color-coded response groups for disaster planning. Representatives of hospitals and fire/paramedic agencies in each group meet regularly to plan their required mass casualty drills and to critique them. Seven hospitals in north Orange County, including St. Jude, made up the Brown Net grouping in 1980.

Pleased with our drill performance, St. Jude's Disaster/Safety Coordinator asked me to come to the next Brown Net Disaster Committee meeting to talk about what had happened in the phone outage and what we did in the drill. Once again, I was ready to wave the banner of Amateur Radio, but I still had not quite grasped the bigger picture. With great enthusiasm, I touted the value of Amateur Radio in the aftermath of disasters such as the 1964 Alaska earthquake and recent tornadoes in the Midwest. Then I described the phone outage and what we did in the drill. Every hospital representative in attendance had questions, but the one that launched me on a 30-year path was, "We don't have someone like you working at our hospital every day. How do we get hams when we need them?"

As the meeting ended, all seven hospital representatives wanted Amateur Radio operators to be on call for their facilities. The Disaster Coordinator from a hospital at the eastern boundary of the county, along the banks of the Santa Ana River and downstream from Prado Dam, had an even greater concern. "We're pretty far away from the major part of the county," he said. "Who will think of helping us in an earthquake or other disaster when all the phones are out? We have the new HEAR radio, but sometimes it goes down and it certainly could be inoperable after an earthquake."

I realized that I had just done a great sales pitch, but I didn't really have a "product" to provide at that time. I wasn't prepared to tell these hospitals just how Amateur Radio would support them, so I started by giving them my name and phone numbers and said I would be getting back to them with a plan. In the meantime, they could call me in the event of a communications problem.

I wasn't very comfortable with that response. What if I wasn't around when communications failed? If I got an emergency call, was I going to just jump on the repeater again and ask for help? Yikes! What if it was at 2 AM? Would I know the responding hams? Would they be prepared? How would we be activated by hospitals if there were an earthquake and all the phones went down?

I asked for a follow-up meeting with the ARES area EC to explain what I was being asked to do. He quickly appointed me as an Assistant Emergency Coordinator to organize a response plan for the requesting hospitals. We had already learned some lessons that would start us into our planning, but the "How do we get hams?" question troubled me. The other question, "Who will think about our hospital in a major disaster?," bothered me even more.

My own hospital had an HF station and I had my 2 meter radio with me on the day we lost our phones. But just installing some equipment at hospitals would not constitute a real plan. Finding hospital employees with an Amateur Radio licenses wouldn't be an adequate plan, either. I'd already encountered one hospital employee with a ham license, but he wasn't active in the hobby and had no equipment at the time. We had known about the drill well in advance and the hams were already on site at the start of the simulation. That didn't test how we would be activated for an actual mass-casualty incident, nor did it test what it would be like to activate, get into the hospital and get started in real time.

The need was clear. Orange County ARES would have to create a robust activation procedure for the hospitals. I was around much of the time, but not 24/7/365. There had to be persons in addition to me as points of contact. Whom could I rely on to come help at a hospital? Having been through the phone outage, I knew well that there was a wide range of preparedness, knowledge and experience among hams. Being a patient care person, I knew the hospitals' concerns for privacy. I also knew that a hospital is a specialized and technical environment. It was obvious that education would be important for radio operators wanting to help there, to avoid mistakes or misunderstandings. In a hospital, "PTT" does not mean "push to talk." "Quad" does not refer to an antenna.

The early lessons had indeed been learned and now it was time to get to work. A special group of Amateur Radio operators interested in this aspect of the Amateur Radio Emergency Service must be formed. An activation procedure must be devised for each hospital to use. Response to multiple hospitals in major area-wide disasters must be planned. Training must take place so that responders would be prepared and knowledgeable.

There was plenty to do but little did anyone realize what lay ahead. We had far more yet to experience, learn, and accomplish.

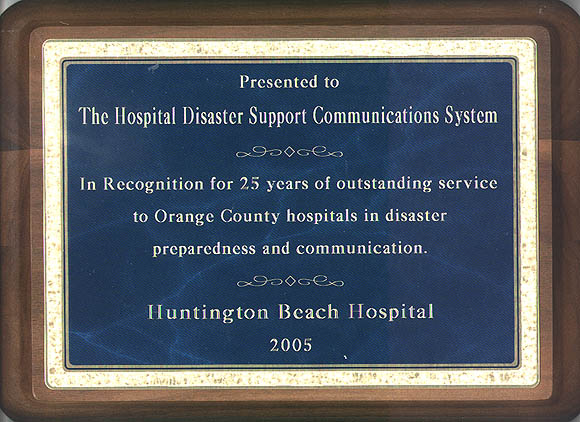

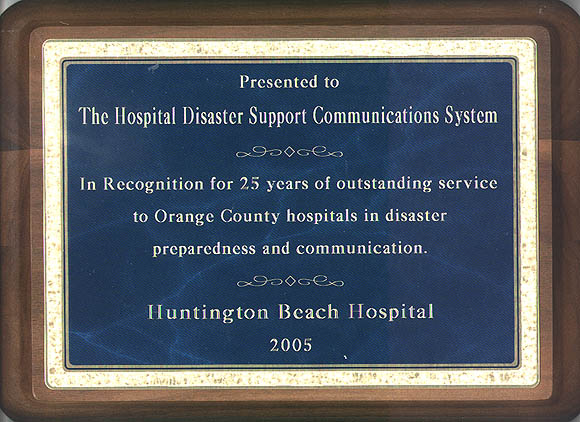

At the annual HDSCS Orientation and Review Workshop in March 2010, Mike Steinkraus N6PTN, Medical Disaster Management Coordinator of Orange County Emergency Medical Services Agency, presented a certificate to the HDSCS in recognition of its 30 years of service to the medical communications needs of the county.

Back to the HDSCS home page

This page updated 12 January 2015